Next Tuesday, the 25th of July, we will be hosting our final revolutionary workshop in east Co. Limerick. The workshop is free to attend and will be held in Kilmallock Library. Since it will be in the Kilmallock area we thought we’d focus our latest blog on an incident that occurred less than 10km north west of the town in Ballingaddy, Co. Limerick.

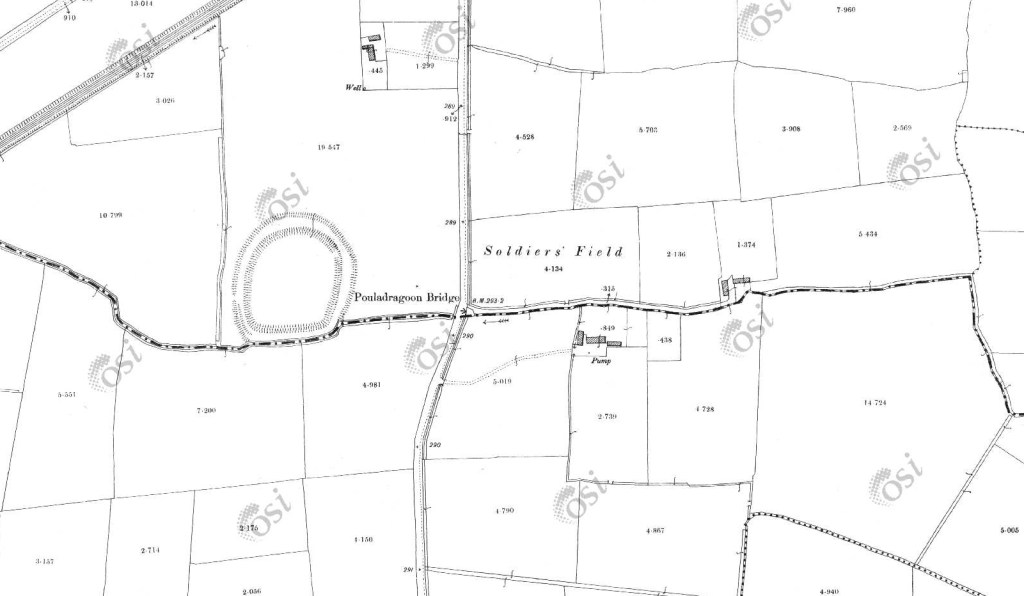

Those familiar with the area might know the field known historically as the ‘Soldiers’ Field’. It is located located a short distance south of the Kilmallock-Charleville road and about a mile west of St Mary’s Church, Ballingaddy. The field’s name may sound like it was part of county Limerick’s War of Independence or Civil War but it actually predates them.

On a road a few fields futher south of the ‘Soldiers’ Field’ is where a tragic event took place during the Civil War. believed to be where the three National Army soldiers were possibly killed in action on Monday, July 24, 1922. The soldiers were with an advance scouting party that came under heavy fire from the anti-Treaty IRA who occupied the area.

Such deadly skirmishes were all too common around the so-called ‘Kilmallock Triangle’, an area

that also included the districts around Bruff and Bruree, in the final weeks of July and early days

of August 1922. Military control of Kilmallock had become central to the Civil War in the south

of Ireland following the capture of Limerick city by pro-Treaty National Army forces just days

before the incident at Ballingaddy.

The National Army concentrated major resources – but also suffered significant losses – in this

part of the IRA’s old East Limerick Brigade area, in its effort to push retreating anti-Treaty

fighters further south. The incident near Ballingaddy on the 24th of July came a day after almost 40

National Army troops were captured in two engagements in the area. One happened less than a

mile west along the railway line at Thomastown, where at least one pro-Treaty soldier was

killed.

Locating exactly where such events in the Irish Revolution took place can be narrowed down

significantly through research with old maps, newspapers, local history publications, or

documents in archives or family possession. But the Archaeology of the Irish Revolution in East

Limerick project depends on – and has enjoyed already – the kind of knowledge that only those

local to an area can provide about events over a century ago. Even if it is second-hand or third-

hand information, handed down by deceased releatives or old neighbours, it can help us decipher

if a field boundary or safehouse described in a written account was on the north or south side of

the road, or which of a townland’s three streams was referred to in a hastily-written military

report.

With the Ballingaddy incident, we are helped enormously by contemporary on-the-ground

evidence from a reporter with The Irish Times embedded with the National Army. They were

moving along a road a quarter-mile south of the railway line, when anti-Treaty positions were

first discovered by an officer who had gone about 50 yards ahead of the advance section with

which the journalist was travelling.

“Rounding a curve in the road, he came straight up against a barricade,” he wrote in a report

published a few days later. This section of “hollow road” with high edges on either side, was where the army scouting section came under attack. It could be where the road straightens out after a bend immediately south of Pouladragoon Bridge, seen in the map immediately east of the distinctive round shape of remains of a medieval moated house. This is the location suggested by Mainchín Seoighe in his

book, The Story of Kilmallock.

PICTURE Curve in road south of rail line at Gortboy – another possible location of July 1922

ambush on National Army

But it is also possible that the action took place in Gortboy, where a much more pronounced

bend appears to better match the narrative provided in the newspaper.

Knowing the exact location with certainty would help piece together and map the actions and

movements of both sides in the episode and across these important few days. Such understanding

of combatants’ movements is an essential element of battlefield archaeology. Having this

knowledge would supplement the detailed account provided by The Irish Times, whose reporter

described the moments immediately before the burst of anti-Treaty machine-gun fire that almost

certainly caused the National Army fatalities. He wrote, with sadly-accurate prescience, that he

and the troops with whom he was taking shelter behind thick hedges were “remarkably like rats

in the proverbial cage.”

This problem of locationary evidence is often more difficult when it comes to the Civil War, for

many reasons – and not just because of the greater reticence that veterans invariably felt about

speaking of events in this conflict than about their War of Independence experiences. The

combatants in the June 1922-May 1923 war were very often not local to the area where they

fought. This was particularly true of those from the National Army side, who were generally

drawn from around the country to provide military assistance to the Provisional Government in

the most fiercely-contested counties and districts.

In the Battle for Kilmallock, fighters on both sides were more likely than not to come from

counties other than Limerick. And in the case of this incident near Ballingaddy on a Monday

afternoon in July 1922, that was very much the case.

Bruff, Co. Limerick

Bruff, Co. Limerick

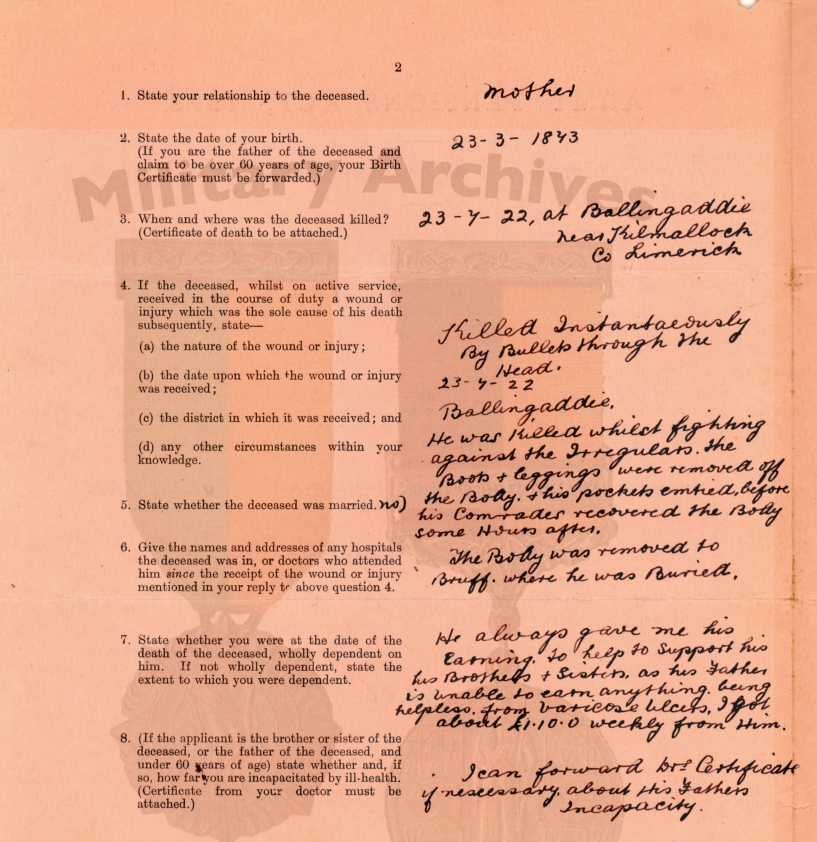

The dead men included Timothy Murphy, a 19-year-old National Army private from near Gneeveguilla in north-west Kerry. One of his fellow-fatalities, Cornelius Sullivan, was a Corporal from outside Scartaglen, Co. Kerry about 10 miles from where Murphy grew up. Although no roadside markers record the area where the battle took place, reminders of the event are to be found in Teamplin cemetery, Bruff, Co. Limerick. The remains of Timothy Murphy and Cornelius Sullivan were laid to rest here, but those of the third dead soldier, Private Quirke, were later exhumed and reburied in his native Kerry.

She also referred to the treatment of the soldiers after they died, writing that “The boots + leggings were removed off the Body + his pockets emptied, before his comrades recovered the body some hours after.” Although this account, likely true, and a later official National Army report to their headquarters suggest disrespect to the deceased (and the army report even indicates the men were captured and then killed as prisoners), other contemporary evidence offers an alternative view. The reporter was with those who retrieved the bodies in the early hours of the following morning on

the roadside where they died. He indicated they were likely among “a bunch” of soldiers he saw on the road right below him shortly before retreating, who he had noted were “a lot too much crowded together, and one burst would finish them.” When the bodies were recovered, the anti-Treaty forces had “composed the bodies and placed their [Rosary] beads in their folded hands.” The bodies were then carried by cart to a local National Army headquarters, and later by ambulance to a position further back from where military action was continuing. From information received at one of our previous Archaeology of the Irish Revolution in East Limerick workshops, we believe we have identified one of these locations. A workshop participant told us how a relative, now deceased, remembered as a child seeing dead men’s bodies on a cart outside the family farmhouse which had been commandeered by a military group. The timeline and location match those of where these National Army soldiers’ remains

would have been brought after the incident near Ballingaddy in the early hours of July 25, 1922.

On the same date as the ambush but 101 years later, we will hold our latest and final Archaeology of the Irish Revolution community workshop. We would love to see you come with stories, artefacts, or documents relating to the War of Independence or the Civil War period in East County Limerick. Maybe you or someone you know who lives in this Kilmallock Triangle around the Kilmallock, Bruffor Bruree areas – or had family there a century ago – has more information about the Ballingaddy or Thomastown incidents or other events. It could be the location of a safe house, a ditch where combatants on any side in the conflicts hid or fired from, or a photo or medal associated with someone involved. Whatever it is, we would love to hear from you. The final revolutionary workshop will be held in Kilmallock Library on Tuesday the 25th of July at 7 pm.

This blog was written by Archaeology of the Irish Revolution historian Niall Murray

***

The Archaeology of the Irish Revolution in East Limerick project is funded by the Irish Research Council COALESCE fund, which funds excellent research addressing national and European-global challenges across a number of strands. This project is part of the INSTAR+ awards, funded by the National Monuments Service of the Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage in partnership with the Heritage Council. It is being undertaken by University College Dublin School of Archaeology in partnership with Abarta Heritage. Other partners on the project include Dr Damian Shiels, the National Museum of Ireland, Limerick Museum, Heritage Maps, and local historians of the War of Independence and Civil War eras.